Originally from ARTISTIC JAPAN (LE JAPON ARTISTIQUE): Siegfried Bing PUBLISHER

Written by L. FALIZE and Published in the late 1890s for ARTISTIC JAPAN

In approaching the Art of Japan, it is not my intention to touch upon its origin or its marvels, or to ascertain the laws upon which it is founded. A goldsmith myself, I shall confine myself to a short dissertation on the Art of that craft as practiced in Japan.

Japan, correctly speaking, has neither the art of the goldsmith nor of the jeweller (sp.). The males do not, like the Indians, deck themselves out in jewellery, nor do the females wear collars or bracelets ; no vessels of silver are found upon their tables, nor vases of gold upon their altars. From this it will be seen that no comparison can be formed between them and us in this respect, and it would be puerile to attempt to assign a preference to the work of either. Originated for dissimilar wants, governed by other laws, this branch of Art followed, in Japan, traditions of so different a nature that it is impossible to compare either the form, the decoration, or the style with anything Western.

Japan, correctly speaking, has neither the art of the goldsmith nor of the jeweller (sp.). The males do not, like the Indians, deck themselves out in jewellery, nor do the females wear collars or bracelets ; no vessels of silver are found upon their tables, nor vases of gold upon their altars. From this it will be seen that no comparison can be formed between them and us in this respect, and it would be puerile to attempt to assign a preference to the work of either. Originated for dissimilar wants, governed by other laws, this branch of Art followed, in Japan, traditions of so different a nature that it is impossible to compare either the form, the decoration, or the style with anything Western.

This, notwithstanding, it is impossible not to admire in Japanese jewellery, or rather in the products of the worker in metals, a taste in the arrangement, a science in colouring, and a manual dexterity.

This, notwithstanding, it is impossible not to admire in Japanese jewellery, or rather in the products of the worker in metals, a taste in the arrangement, a science in colouring, and a manual dexterity.

The forms are not derived, as in ours of the old world, from an architectural fount ; if vases occasionally appear to be constructed on certain definite rules, they then most certainly have a Chinese or Corean origin. The Japanese model is always supple; inspired by a flower, a fruit, something in nature, it has never adapted itself to rule or to measurement by the compass, but remains free, picturesque, and daring.

The love of gold or silver, the desire to impart to an object richness and magnificence, has never bound the workman to the exclusive use of those two metals. To him they are merely two colours upon his palette, upon which he has also ranged iron, , copper, lead, pewter, and brass, and these he uses like a painter, mixing and combining his tints, and varying his effects through the use of alloys in a way we have never yet dared to do.

The love of gold or silver, the desire to impart to an object richness and magnificence, has never bound the workman to the exclusive use of those two metals. To him they are merely two colours upon his palette, upon which he has also ranged iron, , copper, lead, pewter, and brass, and these he uses like a painter, mixing and combining his tints, and varying his effects through the use of alloys in a way we have never yet dared to do.

Thus, then, we see this workman artist under no obligation to confine his efforts to hammering out a silver flagon, or shaping a gold ring, but free to model to his liking his mass of metal, and to paint it in all the colours which that metal offers to him. He constructs his model in wax ; it is perchance a rugged trunk of a tree which two hundred years of growth and wear have delved into deep furrows, whose powerful roots grip the ground, which has deep cavities burrowed by generations of insects, which is overgrown with moss or other parasites, some old, some of infantine freshness. All this our artist copies with the patient care of a workman to whom time is of no value. He installs himself in the depths of the forest before his model ; he studies it as a botanist, he gets to understand, love, and admire it. He changes nothing, arranges nothing—or rather disarranges nothing—of what he considers that nature has set out so well, and then, when his wax model is complete to his satisfaction, he coats it with a fine earth ; this he overlays in small pieces, and allows to dry, adding to it wherever necessary, until he has made of it a mould which covers his model with a solid envelopment. He then heats the whole at a small fire in a specially constructed oven ; the wax melts and runs out of the air holes, and the mould remains entire, with its previously constructed core of earth.

patient care of a workman to whom time is of no value. He installs himself in the depths of the forest before his model ; he studies it as a botanist, he gets to understand, love, and admire it. He changes nothing, arranges nothing—or rather disarranges nothing—of what he considers that nature has set out so well, and then, when his wax model is complete to his satisfaction, he coats it with a fine earth ; this he overlays in small pieces, and allows to dry, adding to it wherever necessary, until he has made of it a mould which covers his model with a solid envelopment. He then heats the whole at a small fire in a specially constructed oven ; the wax melts and runs out of the air holes, and the mould remains entire, with its previously constructed core of earth.

Then our artist makes his alloy of shakudo, which is a mixture of copper and gold ; this will subsequently take a patina of intense black, and of a transparent polish ; the metal is poured into the cavity of the mould, and fills it in every part ; the earthen envelope is then broken, and the rugged tree trunk appears in all its metallic beauty.

Our artist now sets to work again, squatting on the ground before his tree model which sits so quietly to him ; shaded by a big parasol, his legs bent under him, he holds the block of bronze between his knees. And now watch him whilst he chisels, files, polishes, returns again and again to the smallest details of his work, and when he has finished it, watch him as he caresses it and rejoices that he has discovered so many beauties, and has been aroused to so much enthusiasm. But even then his task is incomplete ; when he considers that his bronze cast is finished, then he commences to cover it with moss and verdure, or he  furrows up with deep lines the fibres of a root ; this he encrusts either in small planes or in delicate veins with pieces of shinshin (yellow copper), shido (violet copper), or shibuichi (an alloy of six parts of copper and four of silver) ; then he hollows out the contours of the leaves, and carves out small veneers of green gold which he will inlay, hammer, and chisel, until the whole grows like a picture under an artist’s brush, and his sculpture appears, to a near-sighted person, painted -with the fineness of a miniature, and with the delicacy of flesh. Here we see a whole tribe of ants issuing from a hole in the tree ; their bodies are of gold or iron, their legs of extreme tenuity ; endowed with life, they bustle and hurry about their accustomed duties. A golden, enamelled butterfly, whose delicate wings of mother-of-pearl give out reflections as deep and changeable as those of the original, has posed itself upon a white flower of silver, variegated with threads of gold and blue enamel. A curious red spot is visible at the base of the tree ; it is a fungus, striped and spotted, admirable in its modelling ; the patient artist has filed and polished it, and then subjected it to several coatings of red lac, each of which have had to be carefully and slowly dried, repolished, recoated, pricked over with gold dust. And now only (after having gone over all his work a hundred times, which never to his mind will compare with the original, after having clothed it with a coating of adherent silver-leaf, which is itself a mass of admirable design in niello-work, after having baked it in sulphur, polished it with the finest powder, tempered it in a vinegar formed from plums, fired it with infinite precautions, exposing this part, protecting that, after a thousand caresses, and a thousand retouches) does the artist place his signature upon it, satisfied with his work ; then he encloses it first in a covering of embroidered silk which fits it like a garment, and then in a casing of deftly-joined wood. And now at last we see the completedwork, the product of many months of assiduous, impassioned, happy toil, passed in communion with an out-of-theway corner of nature, with its imaginative dreamings, its enchanting life, its delights for the man at once a sculptor, painter, and mechanic.

furrows up with deep lines the fibres of a root ; this he encrusts either in small planes or in delicate veins with pieces of shinshin (yellow copper), shido (violet copper), or shibuichi (an alloy of six parts of copper and four of silver) ; then he hollows out the contours of the leaves, and carves out small veneers of green gold which he will inlay, hammer, and chisel, until the whole grows like a picture under an artist’s brush, and his sculpture appears, to a near-sighted person, painted -with the fineness of a miniature, and with the delicacy of flesh. Here we see a whole tribe of ants issuing from a hole in the tree ; their bodies are of gold or iron, their legs of extreme tenuity ; endowed with life, they bustle and hurry about their accustomed duties. A golden, enamelled butterfly, whose delicate wings of mother-of-pearl give out reflections as deep and changeable as those of the original, has posed itself upon a white flower of silver, variegated with threads of gold and blue enamel. A curious red spot is visible at the base of the tree ; it is a fungus, striped and spotted, admirable in its modelling ; the patient artist has filed and polished it, and then subjected it to several coatings of red lac, each of which have had to be carefully and slowly dried, repolished, recoated, pricked over with gold dust. And now only (after having gone over all his work a hundred times, which never to his mind will compare with the original, after having clothed it with a coating of adherent silver-leaf, which is itself a mass of admirable design in niello-work, after having baked it in sulphur, polished it with the finest powder, tempered it in a vinegar formed from plums, fired it with infinite precautions, exposing this part, protecting that, after a thousand caresses, and a thousand retouches) does the artist place his signature upon it, satisfied with his work ; then he encloses it first in a covering of embroidered silk which fits it like a garment, and then in a casing of deftly-joined wood. And now at last we see the completedwork, the product of many months of assiduous, impassioned, happy toil, passed in communion with an out-of-theway corner of nature, with its imaginative dreamings, its enchanting life, its delights for the man at once a sculptor, painter, and mechanic.

Can this be termed a piece of jewellery? Who is the man who will identify himself here with similar models and work ? I have dwelt at some length upon this patient, determined, capable, poet of the tool, in his open-air studio. For why? Because it is a picture of the workman of old, as he once lived and worked. We cannot, unfortunately, now come across his fellows, for they do not exist. Japan, in its process of civilizing itself, has ceased to produce anything except the articles required for exportation to Western bazaars. Fortunately, however, this great artist of the past has left traditions, sleight-of-hand secrets of the craft, receipts for alloys, methods of creating patinas and of decoration which are still in vogue in the workshops of Kyoto, Osaka, Tokyo, and Nagoya.

It is fortunate that as nowadays the secret is lost of creating a sword-guard similar to those by these renowned artists, there still remains to us the originals of those powerful and charming productions, where the iron is pierced, incised, carved out, tortured into the form of monsters, interlaced into the shape of birds, insects, or flowers, or modelled into a landscape forming a picture no bigger than a child’s hand but containing within itself a complete poem.

It is fortunate that as nowadays the secret is lost of creating a sword-guard similar to those by these renowned artists, there still remains to us the originals of those powerful and charming productions, where the iron is pierced, incised, carved out, tortured into the form of monsters, interlaced into the shape of birds, insects, or flowers, or modelled into a landscape forming a picture no bigger than a child’s hand but containing within itself a complete poem.

Not only is the whole completely modelled, but a damascening of fine gold overruns it, drawing the outlines of feather or scale, and streaking with its colours of warm or cool gold or silver, the rugged iron basis. Perchance a leaf encrusted with green or red attracts with the colouring of an emerald or ruby.

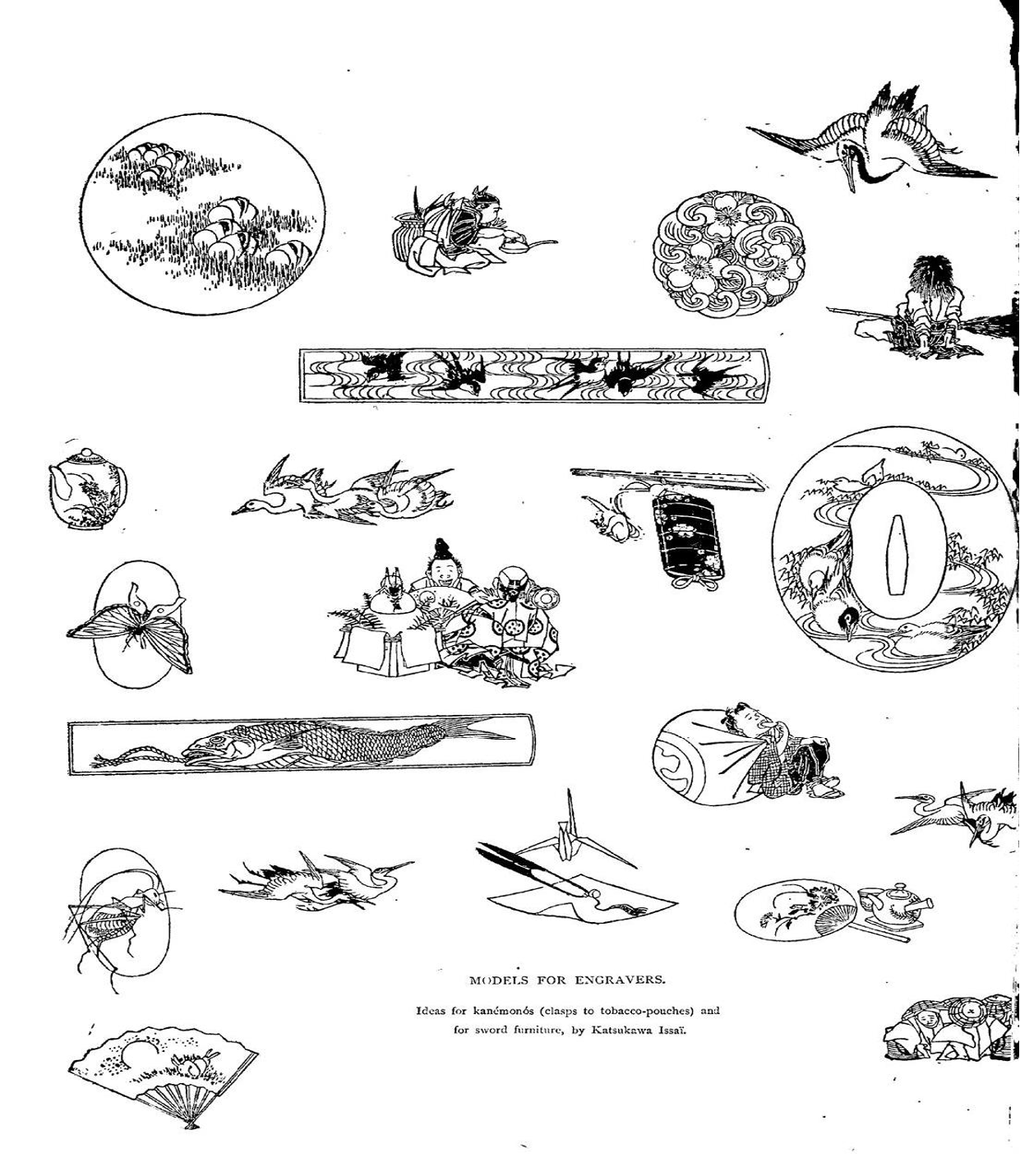

And all this ornamentation was not lavished only on the sword-guard. Even in the interfacings of the cord upon the hilt were to be found the menuki, made of the same metal as the rest of the furniture ; these would represent either some extraordinary animals, or a god, or perchance a singing woman, with her musical instrument, her robe all encrusted with silver, and her hair  of wondrous black metal, and all chased and chiselled under the magnifying glass. Then again there is the pommel of the sword, and the kodzuka and kogai, all replete with ornamentation ! But it is needless to dwell upon these, for probably the majority of those who read these lines know of or possess collections of these wonderful things. And to all these must be added the engraved pipes, the kanemonos, or pouch ornaments, the buttons, and the metal netsukés which rival those in wood and ivory. Besides, the engravings of these things, which will from time to time appear in these pages, will tell far more than any written description.

of wondrous black metal, and all chased and chiselled under the magnifying glass. Then again there is the pommel of the sword, and the kodzuka and kogai, all replete with ornamentation ! But it is needless to dwell upon these, for probably the majority of those who read these lines know of or possess collections of these wonderful things. And to all these must be added the engraved pipes, the kanemonos, or pouch ornaments, the buttons, and the metal netsukés which rival those in wood and ivory. Besides, the engravings of these things, which will from time to time appear in these pages, will tell far more than any written description.

It is now twenty years since, filled with admiration at the first specimens I saw of an art which appeared to me as a tempting novelty and an * unexplained problem, I wished at once to set off to Japan in order to study on the spot this unknown industry. I fondly hoped to be able to carry thence some of their patient and talented workmen in order to make them instructors for our own. I nursed this wise project for several months, and dreamt of all that there was to be found in a country which had yielded us so little as yet. My desire, however, had to contend against a will that was stronger than my own. I did not go, and I have elsewhere explained how I consoled myself by borrowing from Japanese designs the idea of cloisonné enamels which I made, and which has since spread widely. If I had been able to obey the instinct which prompted me, I should have hoped to have been the Apostle of Japan, its Prophet, and a capable translator of its Art. Knowing what I did then, I should have been the first foreigner to examine the Art at its fountain head, with the workman in his pristine condition. I need not speak of the fortune which I feel sure I could have easily made ; I only regret the loss of a journey which would have been full of artistic and novel interest.

Since then I have shown the way to others ; I have told and written of all that I have seen, and what they and I have done. But impelled by the necessities of rapid production, neither they nor I have approached the disheartening perfection of those masters who are acquainted with every metallic alloy, who found, beat out, chisel, engrave, encrust, damascene, enamel, lacquer, polish, patinize, set, and carve with a subtlety of invention, a taste for decoration, a variety of motives, a harmony of colours, and a sense of form, and who are, in the opinion of our profession, artist workmen whose productions in metal are simply adorable.

Since then I have shown the way to others ; I have told and written of all that I have seen, and what they and I have done. But impelled by the necessities of rapid production, neither they nor I have approached the disheartening perfection of those masters who are acquainted with every metallic alloy, who found, beat out, chisel, engrave, encrust, damascene, enamel, lacquer, polish, patinize, set, and carve with a subtlety of invention, a taste for decoration, a variety of motives, a harmony of colours, and a sense of form, and who are, in the opinion of our profession, artist workmen whose productions in metal are simply adorable.

I believe that it will be worth while to examine the subject yet closer, and this I hope soon to do in these columns from a purely industrial and special point of view.

I believe that it will be worth while to examine the subject yet closer, and this I hope soon to do in these columns from a purely industrial and special point of view.

FALIZE.

END

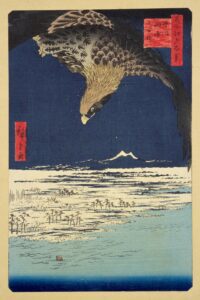

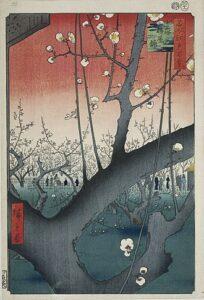

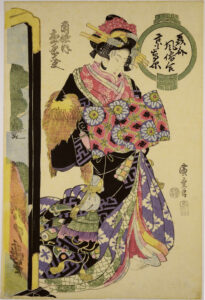

jpwoodblocks is the leader in Japanese woodblock prints on the internet. We have the widest selection of Japanese woodblock print knowledge base, including Archives of Hiroshige, Hokusai, Hasui, Yoshitoshi, Koson, and more. We are constantly expanding our offerings to you and wish to curate the top Japanese Woodblock Print art center in the world. If you are interested in learning more, be sure to check back to our website frequently – and be sure to check out our latest collection of Japanese woodblock prints for sale. And if you have a woodblock print you would like to sell, please get in touch.

THANK YOU for stopping by!