[U-key-oo] ۰Japanese

(n.) Living in the moment

Detached from the bothers of life

“The Floating World”

“The floating world”. Well, without any context this form of art is like a rather arcane and mysterious idea. Believe it or not, Ukiyo-e, or “floating world pictures” is a description of one of the most systematic and multi-faceted art forms we have yet known! So what are these “floating world pictures? And why in the world is there a whole artistic movement surrounding it?

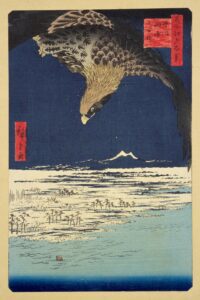

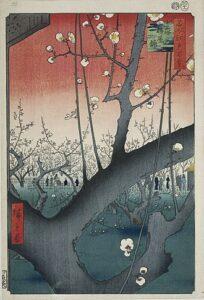

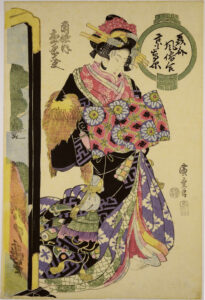

While this form of art began to bloom in 17th-century Japan and flourished throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the term Ukiyo-e dates further back. A Buddhist term used to describe the “spur of the moment” nature of life and its events, the term Ukiyo-e was ironically applied to Yoshiwara, an entertained district in Japan, loaded with brothels, tea houses, and mansions for wealthy Japanese men to spend the day with Geishas and Oirans (courtesans in Japanese culture) of their liking – so a literal floating world for the rich, you could say[2]. This essence of the term was often captured in the Japanese woodblock prints through colorful imagery as the art form began to evolve over time.

Onto the more historical aspect, Japanese woodblock art or Ukiyo-e was born in a historically significant period for Japan, right after the battle of Sekigahara- where an army of 160,000 men lead Tokugawa Leyasu to become the next emperor and the commencement of what was famously known as the Edo Period[4]. The Tokugawa clan established Edo (now Tokyo) sd their cap and transformed it into one of the largest and most diverse Metropolitan cities across the globe. The country also banned all foreign entry and trade with the country at the time[1]. And while this severed all their ties with the rest of the world, it gave Japanese artists room to think outside the box and develop a unique nest of woodblock art that we now know and love today. With Japan moving to a more urban form of living during this period, the merchant class began to gain wealth, and art became a more accessible form of expression, unlike previous eras where it was associated with the upperclassmen and Samurai. And especially woodblock art, Tokugawa Ieyasu’s inauguration of the Renpi school of art in Kyoto was quite the turning point, as more and more individuals began to pursue art right after[5].

The original idea of Japanese woodblock prints evolved from the development of a wooden, movable printing press instead of a metal one in the initial days of Tokugawa’s reign during the Edo period. Soon after this craftsmen and artists came to the realization that the flow of the Japanese script would be more appealing and effective instead of print. Needless to say, woodblock became a commercial commodity and was used for everything and anything by the 1640s. Japanese Ukiyo-e has evolved tremendously ever since. From just human figures of different kinds during the 17th century by Hiroshige and Hokusai to multicolored paintings Nishiki-e by Suzuki Harunobu and the latest works of Yoshitoshi, you can’t turn a blind eye to how vast this branch of art has become. To surprise you, even more, a large majority of European modern art is also based on Japanese woodblock art[3]. In fact, our favorite painter, Van Gogh was the biggest fan and Japanese art collector you’d find in Europe!

Moving on to the techniques of making a Japanese woodblock masterpiece, woodblock print images are often first traced on a transparent sheet of paper, followed by carving along those lines on cherry wood. The surface of the woodblock is then covered in ink and stamped onto a piece of paper using a round pad. Now that’s a standard monochromatic woodblock art piece. But what about multicolored ones? A very simple solution, make several separate woodblock pieces, each with the color you want. And then stamp there where you like on your paper. You might also ask what type of paper to use[1]. Really any type of paper works, but getting your hands on paper made from mulberry bark is the ideal kind.

As you probably would have guessed, this isn’t a single-person job. Every Ukiyo-e woodblock print involves at least four professionals: a publisher, the artist, the wood-cutter, and a printing press individual (call him a printer if you will). The publisher commissions the artist to prepare a sketch or a shita-e[5]. This is then traced on very thin paper, which is then pasted onto a cherry wood block. The printing guy would then cut through the paper, leaving just the outlines of the design in black ink. The cutter then chisels the design into the woodblock by rubbing the inked paper onto it. The artist then gets the chiseled wood block back and marks it with all the colors that he wants. Finally, the printer relieves the finished piece of woodblock and prints it onto paper. Phew, that sounded long, didn’t it? Well, it is. But the Japanese have been doing it for so many years now that it’s safe to say that they’ve become pros at it. And eyes on the prize of course. This systematic process does work indeed and has blessed the world with remarkable artwork.

So the next time you see a woodblock print, you’d see it in a whole new light now, won’t you? Well, we hope so!

References:

- Metmuseum.org, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ukiy/hd_ukiy.htm.

- Metmuseum.org, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ukiy/hd_ukiy.htm#:~:text=Ink%20is%20applied%20to%20the,could%20number%20up%20to%20twenty

- “How Were Woodblock Prints Made? • Japanese Woodblock Print.” How Were Woodblock Prints Made? • Japanese Woodblock Print • MyLearning, https://www.mylearning.org/stories/japanese-woodblock-print/24

- “V&A · Japanese Woodblock Prints (Ukiyo-e).” Victoria and Albert Museum, https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/japanese-woodblock-prints-ukiyo-e

- Wanczura, Dieter. “Woodblock Prints – History and Techniques.” Artelino, Artelino GmbH, 8 Nov. 2020, https://www.artelino.com/articles/woodblock-prints.asp.