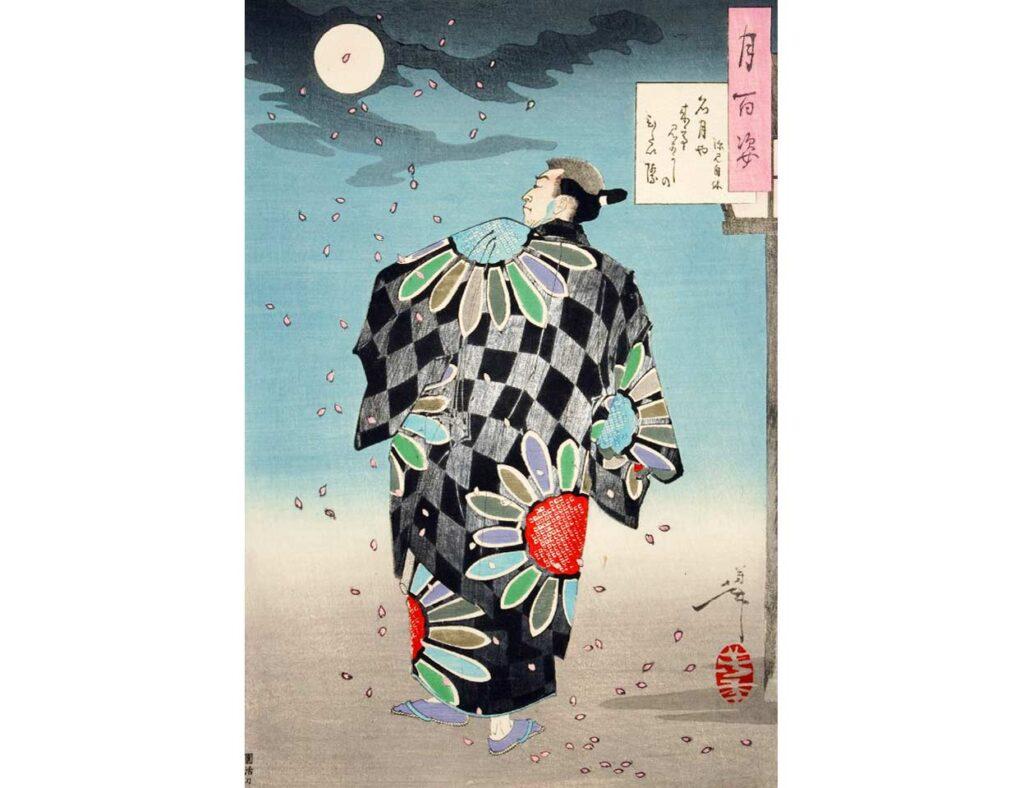

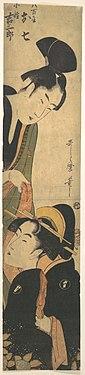

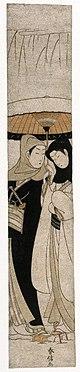

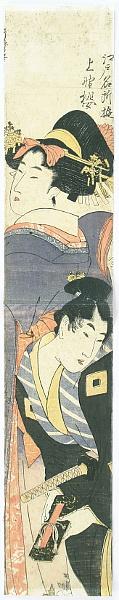

Have you ever wondered what the interiors of walls looked like in Edo? Well, here’s a story. Back in the second half of the 18th century in Edo, when all borders and connections to the outside were severed and ukiyo-e i.e. Japanese woodblock art was in full bloom, there were some artists who thought of experimenting with the size of Japanese woodblock prints. And one type of print that came out of it was Hashira-e i.e. prints with portrait dimensions of 4.5 x 28 inches [1]. To put this into perspective, that’s almost the height of a human baby and width as much as the shoe size of a baby. So to say the least, these prints were relatively narrow. Needless to say, they became wall hangings soon after they first surfaced. A cheap alternative for scroll hangings, these prints became widespread in every house and building of Edo i.e. every household owned at least one such print that hung around their place as a decorative piece [2].

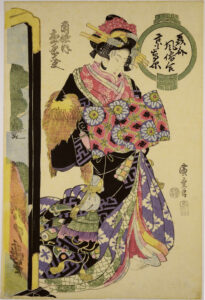

So where and how did these prints first surface? Masanobu Okumura, a Japanese woodblock artist in Edo is known to have popularized these prints in the late 18th century. Although less known to the public, Okumura also specialized in Bijin-ga i.e. imagery of courtesans, and war prints in particular [1]. But around the time when every Japanese woodblock artist had taken up these categories of prints, Okumura decided to take a different road i.e. to experiment with the sizes that these prints could be laid out in. And out came hashira-e – incredibly narrow prints, but with no compromise on how detailed the imagery was compared to the standard size ukiyo-e. Another name who played around with these prints was ukiyo-e artist Koryūsai, who attempted to depict scenes of gods as well as beautiful oirans and geishas of Edo in these tall, thin prints [1]. These prints were later combined into triptychs and diptychs and only a few of them survived in their original form [2]. Nevertheless, you could still say that triptychs and diptychs are a combination of hashira-e since each panel is still made separately. Some prints also retained the same dimension ratio but increased in overall panel size as the years progressed.

As you can probably imagine, it is rather rare to find hashira-e in good condition and color. This is owing to the fact that most of them were hung around buildings and urban areas all over Edo [3]. Thus, these prints have seen it all: from smoke, dust, and pollution to increasing urbanization and weather changes, there is nothing in Edo that didn’t breeze through these prints! In other words, the wear and tear on any hashira-e prints that can be found today is a testament to the fact that there are years and years of history hidden in those cracks and layers of soot [3]. Thus, there is a very high chance that when you come across hashira-e while searching for a Japanese woodblock print to buy, it will either be expensive or a tad bit worn out owing to the circumstances they’ve seen.

Links

[1] Hockley, Allen (2003). The Prints of Isoda Koryūsai: Floating World Culture and Its Consumers in Eighteenth-century Japan. University of Washington Press.

[2] Dieter Wanczura. “What are Hashira-e?”. Artelino. Retrieved 1 November 2020.