A SPECIAL BLOG ENTRY & SERIES FROM THE ORIGINAL ARTISTIC JAPAN PUBLICATION – LE JAPON ARTISTIQUE

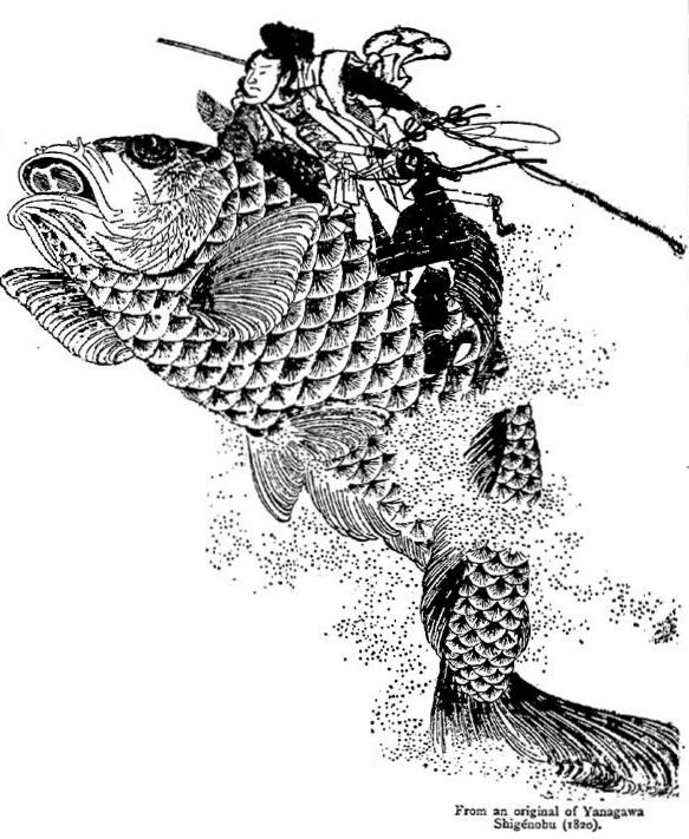

JAPANESE AS DECORATORS by LOUIS GONSE.

I have elsewhere expressed my opinion on the artistic genius of the Japanese, and have said plainly that they are the greatest decorators in the world. This very decided verdict requires explanation and elucidation, and this should not be inappropriate in a publication especially designed to introduce the knowledge of, and do honour to the Art of Japan. I am therefore grateful to M. Bing for having given me the opportunity of unfolding shortly my opinion on a subject that for a long time has deeply engrossed me. When I said that the  Japanese were the greatest decorators in the world, I did not by any means intend to throw discredit on the decorative art of other nations, or to disparage the merit of productions whose artistic value is universally accepted. Such products as Persian pottery, Gothic stained glass, Venetian stuffs of the fifteenth century, and French furniture of the eighteenth century, will always remain works of real beauty, to which no others of their kind will ever be preferred. But I would draw attention to the fact that a feeling for decorative art is born in the Japanese.

Japanese were the greatest decorators in the world, I did not by any means intend to throw discredit on the decorative art of other nations, or to disparage the merit of productions whose artistic value is universally accepted. Such products as Persian pottery, Gothic stained glass, Venetian stuffs of the fifteenth century, and French furniture of the eighteenth century, will always remain works of real beauty, to which no others of their kind will ever be preferred. But I would draw attention to the fact that a feeling for decorative art is born in the Japanese.

Always and everywhere he makes an object worthy of a decorator, and I here use the word “ decorator ” in its noblest and most exalted sense. Art exists for him as something more than a creation to enhance the morality of life : it is to him a mental and physical luxury which is intended by its refinement to increase our satisfaction in living. In the same way in the higher and more severe spheres, those, of religious or historical art, the Japanese artist submits to the ordinances of education which compel him first of all to please the eye before exciting and charming the intellect. He subordinates himself without any apparent effort, and as if it was inherent in his nature, to all the canons of taste. It is necessary to think of this in judging and understanding a Japanese work of art, and this applies to the commonest as to the choicest articles. If this is borne in mind, then everything is clear, all explains itself, and all that was inexplicable at first in those creations which are Japanese in style becomes a new object of admiration.

The Japanese has, in common with his brethren belonging to other Oriental races, an innate decorative sense ; but in his case it is assisted and refined by a clear conception of the beauty of nature, by the influence of customs of ancient date, and many other complex causes—such, for instance, as his method of writing, and even of holding the brush. These have enabled him to exercise to the extremest limits this decorative capacity.

This sense has been still further sharpened by a natural taste for synthesis, by a marvellous instinct for the resources of colour, a thorough knowledge of colour harmony, and a delicate perception as to itsemployment. This unique if .1 concurrence of qualities has made the Japanese the most thoroughly qualified nation to take Art into the usages of everyday life, for the ornamentation of the home it has made them devotees of luxury, ornament, grace, and originality in decoration. It is this predominance over other races as regards the decorative principle in every phase of Art, that has given me ground for asserting that the Japanese are the greatest decorators of the world.

made the Japanese the most thoroughly qualified nation to take Art into the usages of everyday life, for the ornamentation of the home it has made them devotees of luxury, ornament, grace, and originality in decoration. It is this predominance over other races as regards the decorative principle in every phase of Art, that has given me ground for asserting that the Japanese are the greatest decorators of the world.

Although I myself do not know how sufficiently to praise this phase in their artistic genius, I am well aware that by some it is used as an argument in diminution of their artistic capacity. To such as these, this power of design ought to add psychological and quasi-literary suggestions which should increase its value. This is the point of view of the aesthetic of the Arian races, and we by no means wish to speak disparagingly of it. The point of view of the Japanese is more confined; but, once understood, it will seem logical and natural : it suits a people whose physical feelings are refined in the extreme. The consequences of this temperament have had their effect even on the lowest branches of Japanese industry. During the long periods of peace, when the creations of its taste expanded themselves in all their wealth, Japan was, as it were,  seized with a universal dilettantism. In all grades of society, from the most humble workman to the most accomplished prince, thenation seemed to live for the study of Art ; it became, one might almost say, possessed by an inherent love for the beautiful. Greece alone offers a parallel example of so pure and complete an enthusiasm for the pleasures of imagination and the continuous exercise of the aesthetic faculties.

seized with a universal dilettantism. In all grades of society, from the most humble workman to the most accomplished prince, thenation seemed to live for the study of Art ; it became, one might almost say, possessed by an inherent love for the beautiful. Greece alone offers a parallel example of so pure and complete an enthusiasm for the pleasures of imagination and the continuous exercise of the aesthetic faculties.

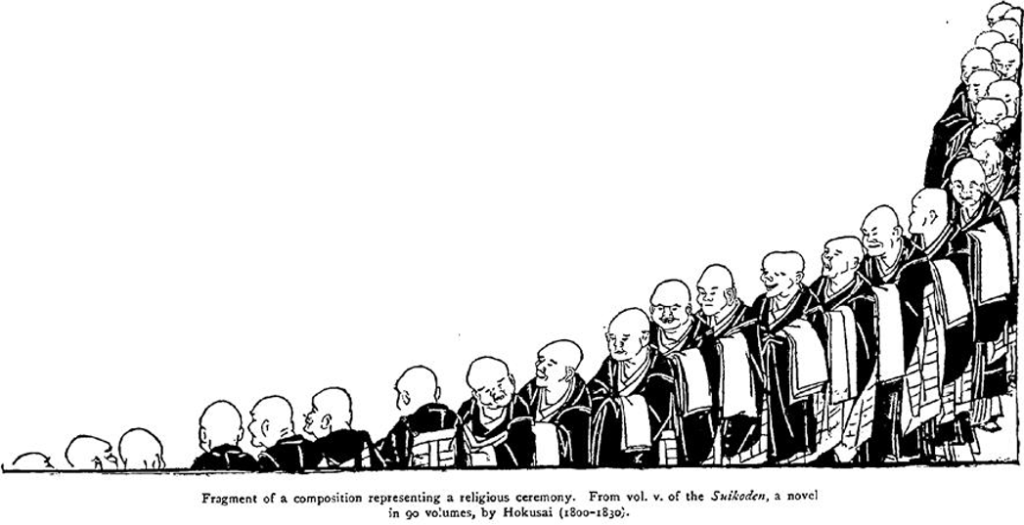

Religious art, so far as regards the branches of painting and sculpture, does not evidence in so marked a degree the same love of the beautiful, but still in outward form it witnesses in many ways to the Japanese taste for decoration. The great pictures of the temple, the ‘ . Buddhist rolls with their dead-gold ornaments in the style of old miniatures and with their costly mountings, .the figures of bronze with their graceful outline and reposeful attitudes—all the apparatus of that highly spiritual conception, the religion of Buddha, is marvellously sympathetic to the general idea of giving pleasure to the eye. In addition to all this, the pomp of ancient ceremonies, the unequalled splendour of the vestments of the priests, and around all the colouring of the architectural frame, and we shall have some idea of the refinement which this nation of artists imparted even to the minutest details of the exercise of its religion.

costly mountings, .the figures of bronze with their graceful outline and reposeful attitudes—all the apparatus of that highly spiritual conception, the religion of Buddha, is marvellously sympathetic to the general idea of giving pleasure to the eye. In addition to all this, the pomp of ancient ceremonies, the unequalled splendour of the vestments of the priests, and around all the colouring of the architectural frame, and we shall have some idea of the refinement which this nation of artists imparted even to the minutest details of the exercise of its religion.

The Japanese have nowhere given fuller play to their delight in harmonising colours than in the construction of their temples—Buddhist or Shintoist. It is by the thought bestowed upon this decoration, much more than by the structures themselves, that the religious architecture of the Japanese recommends itself to the notice of the foreigner. From whatever point it is regarded, it seems the natural complement of the landscape ; it associates itself like a living organism ; it is quite in keeping with the luxurious vegetation which envelops it, the free growth of which the Japanese take delight in, as making a picture essentially picturesque. Trees, rocks, and water play their part in the symphony. It is in the midst of the choicest scenery that the Japanese delights to see elegant porticos raising their graceful outline, arrangements of lanterns, bronze vases, chapels with wonderfully carved roofs, and pagodas in red lac, whose brilliant colours contrast with the green of the pine trees.

It is by this perfect accord between the framework and the picture that the aesthetic rightness of Japanese Art so strikingly affirms itself. According to this sequence of ideas, the artists of Japan have produced work unequalled in beauty. Look at the Temple of Nikko for instance, which was raised in the seventeenth century by the Shogun Yemitsu to the memory of Yeyas, and see whether it was not designed quite as much for the general effect — as a picturesque mise en scène, as we should say—as for its richness of ornament. But what is true with regard to religious art is much more so with regard to profane and familiar art. The Japanese painter in designing a kakémono or wall-painting always starts by remembering its particular decorative purpose, and thinks of it only as a roll of silk or paper made to beautify the walls of a house. He knows that to look well on the walls of a house it must not stand out as a spot, it must be easily read from a distance, and it must at the same time have a quiet effect in the subdued light.

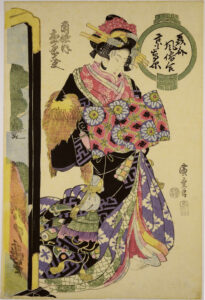

The ormulas laid down by the old masters have been carried on unchanged to modern times, namely, a simple design, simple forms, a studied absence of light and shade, employment of water colours, and lightness of execution. One or two kakémonos hung on the wooden divisions of the house, a pair of movable screens, decorated like the kakémonos, With some pleasant subject, a flower-vase or two, a few commonplace objects in bronze or china, were deemed sufficient by a Japanese of distinction for the decoration of the chamber where he received his guests. It is remarkable that the Japanese will have nothing to do with an object which does not answer some particular use; he does not understand the use of anything which serves the purpose merely of an art object; he is not a collector in the European sense of the word ; he cannot bear useless “curios”; he likes in his home, air, light, and plenty of space. But all the articles used in the everyday life of the Japanese, or which form part of his costume, are designed so as to assume the most varied forms, and they become either by their intrinsic value, technical perfection, or the taste bestowed upon them, works of Art in the highest meaning of the acceptation.

commonplace objects in bronze or china, were deemed sufficient by a Japanese of distinction for the decoration of the chamber where he received his guests. It is remarkable that the Japanese will have nothing to do with an object which does not answer some particular use; he does not understand the use of anything which serves the purpose merely of an art object; he is not a collector in the European sense of the word ; he cannot bear useless “curios”; he likes in his home, air, light, and plenty of space. But all the articles used in the everyday life of the Japanese, or which form part of his costume, are designed so as to assume the most varied forms, and they become either by their intrinsic value, technical perfection, or the taste bestowed upon them, works of Art in the highest meaning of the acceptation.

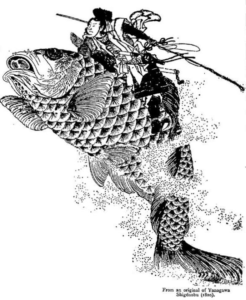

But we are trenching upon the domain of industrial art—an illimitable subject, wherein the power of invention shown is astounding: lacquer, fabrics, chasing, pottery, engraving—all become marvellous through the fairy touch of these artists. Here the genius of the Japanese must provoke admiration, for nothing seems to have escaped them that a subtle instinct for decoration would have conceived. They have experimented with all forms, all combinations, all contrasts of colour, and everywhere they have given proof of the greatest taste and the most rational feeling. Those who only know Japanese Art from ‘ the wretched modern products, so feeble in every way, will perhaps smile at my praise ; those, on the contrary, who love Japanese Art, and have had chances of seeing authentic work of the best time, will understand and, I hope, agree with me. The collections formed by the amateurs of Paris, London, and New York give us, happily, arguments of irresistible eloquence, for nowhere else can one find such numerous specimens of the choicest work. Their examination will show us better than all reasoning the variety and ingenuity of the Japanese decorators. Every effort, every repetition, every reproduction, is new, original, fresh, in perfect sympathy with nature, object, and material, and, as it were, animated with a free and airy grace. Yes, I repeat it, the Japanese are the greatest decorators of the world.

They may have failed to adequately translate the beauties of the human form, or the heights and depths of portraiture, but they have carried picturesque treatment of line and colour further than any other race.

I shall hope to return to some of the points that I have just glanced at here, and show some of the lessons to be learnt from them.