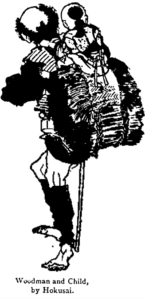

Alas, our enumeration of the contents of the Man-gwa must be but dry and much abridged ! The Man-gwa is a whole world. One asks what Hokusai can possibly have forgotten. There are no repetitions, no omissions, and the volumes seem of a perfect equality.

Alas, our enumeration of the contents of the Man-gwa must be but dry and much abridged ! The Man-gwa is a whole world. One asks what Hokusai can possibly have forgotten. There are no repetitions, no omissions, and the volumes seem of a perfect equality.

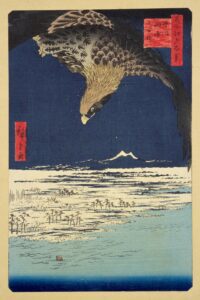

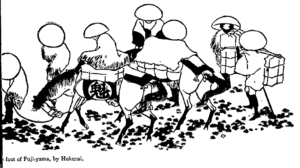

How plainly it shows that, throughout, Hokusai had the intention of being useful ! He devotes several pages to studying the draughtmanship of rocks ; elsewhere he interests himself in the eddies in water, in the manner that leaves are connected with stalks, and in the veins of these leaves. He designs European firearms, carronades, and pistols ; he consigns to his sketch book studies of the effects of ice, mysterious grottoes, tidal waves. He struggles with the rapidity of nature, in portraying geysers, a cyclone, clouds, flames, and even lightning. One sees how he loved movement, he who determined to draw life from beginning to end.  To represent motion was his great ambition. It is not correctness, effect, harmony, but movement itself which he so desperately pursues, sacrificing all to attain this object. This in reality is the chief characteristic of the work of Hokusai—this it is that strikes us most, and—let us confess it at once—it is this that puts us Westerns out of countenance. Our art is entirely opposed to this. It is constructed on the absence of movement, on a sort of perpetual retouching from nature. Movement seems to us a burden upon truth—we mistrust it as an excess, a danger.*

To represent motion was his great ambition. It is not correctness, effect, harmony, but movement itself which he so desperately pursues, sacrificing all to attain this object. This in reality is the chief characteristic of the work of Hokusai—this it is that strikes us most, and—let us confess it at once—it is this that puts us Westerns out of countenance. Our art is entirely opposed to this. It is constructed on the absence of movement, on a sort of perpetual retouching from nature. Movement seems to us a burden upon truth—we mistrust it as an excess, a danger.*

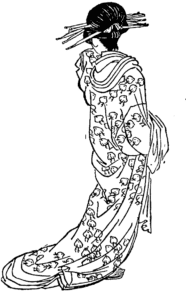

Movement ! It is everywhere in Japanese Art—in architecture, in sculpture, in drawing. Only the Great Buddha is quiescent, and he is so eternally ; but at his feet life multiplies itself, and works in immoderate haste. A swarm of pigmies moves round him—one might say the same of a mad flight of insects dancing in a ray of sunlight round a lotus bloom. Japanese artists delight in liveliness. Stiffness, heaviness, straight lines, logical and carefully set rules are their aversion. They throw themselves recklessly into amusement, only to stop when destitute of breath. Their means of expression, simplified as much as possible, lend themselves admirably to rendering hurried movements and spontaneity of action : as they are minute observers, so they reproduce actions that we take no cognizance of.

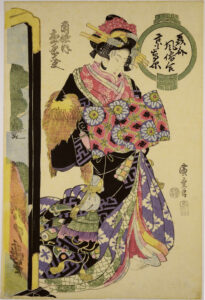

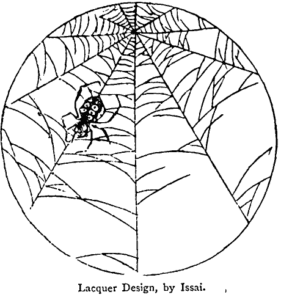

There is nothing in common between the art of the extreme East and ours. The primary matter is different ; curved lines abound, and, above all, perfect symmetry, which is a powerful decorative medium, and constitutes life, movement, freshness, and naturalness. The Japanese paint the physical part of the universe without regarding the fact that they are dealing with the moral part. They do not portray joy, sorrow, love, faith, as we do ; they paint strife, excitement, tragic and comic grimaces.  Humour is with us reserved for the lower styles of art ; in Japan it is one of the elements of the highest art, because humour is produced by movement. The heroes of Japan, thepersonages of romance, like the gods of the Japanese Pantheon, have huge shapes, distorted faces, and highly-strung nerves—all their animal machine participates in action. It is evident that there are two men in the author of the Man-gwa— the naturalistic and the idealistic. One must not be startled by this latter term. Hokusai is not only a lover of visible nature ; he is a dreamer also, an imaginative painter.

Humour is with us reserved for the lower styles of art ; in Japan it is one of the elements of the highest art, because humour is produced by movement. The heroes of Japan, thepersonages of romance, like the gods of the Japanese Pantheon, have huge shapes, distorted faces, and highly-strung nerves—all their animal machine participates in action. It is evident that there are two men in the author of the Man-gwa— the naturalistic and the idealistic. One must not be startled by this latter term. Hokusai is not only a lover of visible nature ; he is a dreamer also, an imaginative painter.

One is inclined, on superficially knowing the art of the East, to consider the great Oriental races as no more than industrious swarms of bees — and with but limited intelligence; a common instinct, we think, animates every individual, but there is nothing out of the usual.  The artists in those regions must produce their works, as bees make honey, by some unknown means. Nevertheless, when a personal wish is felt there, it is the shadow of a thought. The arts of the East are naturalistic, and, above all, decorative, yet in certain cases they play an imaginative part. In the Man-gwa these are side by side with specimens of realistic work, scenes of imagination. The imaginative part has two sources : —

The artists in those regions must produce their works, as bees make honey, by some unknown means. Nevertheless, when a personal wish is felt there, it is the shadow of a thought. The arts of the East are naturalistic, and, above all, decorative, yet in certain cases they play an imaginative part. In the Man-gwa these are side by side with specimens of realistic work, scenes of imagination. The imaginative part has two sources : —

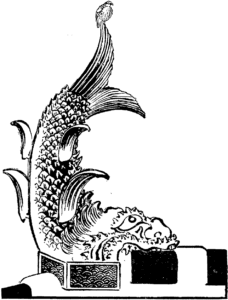

- The ancient religious legends. There exists in the Buddhist religion —so full of serenity and beauty — an unlimited series of demon gods, a Pantheon haunted by infinite devilry.

- The artificial want general in all races, but greatly developed in the Asiatic, to equal Nature in her productions, not being able to equal her in her forces. Such, it seems, is the origin of caricature, which is an idealistic manifestation of art. By a great psychological effort, the Asiatics have created the hideous by studying the laws of the beautiful. They have dreamt of the monster, and have created him also ; they have delighted in their work as a sort of defiance to nature ; they have taken pride in giving the life of artistic work—to that which never existed, to fantastic animal forms, and to human shapes convulsed by unnatural passions.

Hokusai produced dreams, visions, nightmares. These visions have no connection with opium. Here and there we meet such strange pictures in the Man-gwa that we feel inclined to attribute them to the reminiscences of a confused imagination, if we did not know the temperate habits of the Japanese. All that drunkenness reveals to tormented brains—all the forms which smoke can take for a devotee easily worked upon and already affected by the poison — all the exaggerations of the natural—all the ” artificial paradises ” of which Quincey, Poe, and Beaudelaire have instituted themselves trustees—unfold themselves in mad flights full grace or utterly terrible. Is it not remarkable to find in the work of an artist of the extreme East the realisation of those dreams and fancies which the most advanced schools of literature in England and France have believed to be only encountered by them alone ? Who, we ask, is the artist who has made a farther voyage into the unreal world—we were going to say the suggested world?

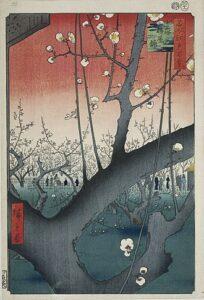

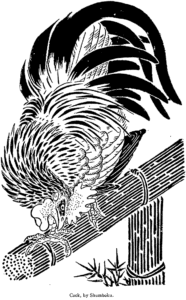

However, Hokusai should remain for us that which he is beyond all—a reporter of nature. When one is contented with a simple outline, without interior modelling, without light and shade, without the artifices of modelling, when one reduces, like the Japanese, one’s means to the very lowest, it is a double triumph, when the strokes must speak for themselves : and it is in this magic that Hokusai is the master. Ingres used to say that one must be able to ” draw with a nail ;” but he knew not the secret of varying, of enriching or diminishing the strokes. The Japanese’s brush has also the full strokes and the thin which have their meaning, and it is often a more manageable instrument than the pencil.  Truly, it paints without colour (which is indicative in woodblock printing), it accentuates, it caresses, it bullies, it glides, it runs, it gallops. It is one of the wonders of our time, almost of the past year or two, that we have given evidence of an eclecticism which enables us to grapple with the arts of a distant and strange country. We are very susceptible in the matter of art, and at the same time somewhat conservative (we have, in some ways, good reason for being so); but here is an absolutely new world, which shows us some of its concealed treasures. When Europe knows them well, and appreciates them better, the verdict will go ” Aye “or ” No ” has too high an estimate been placed upon them ? The Man-gwa is addressed beyond all to the hardworking artisans who maintain our industries. Why do they leave the country, the streams, the fields, the sea ? Why do they not surround themselves with models from nature, brightly coloured and lively ? Why do they not add seaweed, butterflies, a branch of clematis to their limited designs ? If they loved their models as the author of the Man-gwa loved his, they would pass from the rank of artisans to that of artists.

Truly, it paints without colour (which is indicative in woodblock printing), it accentuates, it caresses, it bullies, it glides, it runs, it gallops. It is one of the wonders of our time, almost of the past year or two, that we have given evidence of an eclecticism which enables us to grapple with the arts of a distant and strange country. We are very susceptible in the matter of art, and at the same time somewhat conservative (we have, in some ways, good reason for being so); but here is an absolutely new world, which shows us some of its concealed treasures. When Europe knows them well, and appreciates them better, the verdict will go ” Aye “or ” No ” has too high an estimate been placed upon them ? The Man-gwa is addressed beyond all to the hardworking artisans who maintain our industries. Why do they leave the country, the streams, the fields, the sea ? Why do they not surround themselves with models from nature, brightly coloured and lively ? Why do they not add seaweed, butterflies, a branch of clematis to their limited designs ? If they loved their models as the author of the Man-gwa loved his, they would pass from the rank of artisans to that of artists.

This is what Hokusai taught, in his way, to his compatriots, and it is that he preaches to us now, regardless of time and distance. There is a great difference between the soul of the European and the Asiatic—it is an abyss deeper than the Pacific. But some spirits cross the ocean like birds and the pollen of plants carried on the wings of the wind. The Japanese plant—if I may continue the simile—is as different from the European plant as the chestnut is from the palm or the araucaria. Each one is the natural outcome of certain circumstances, and these circumstances, may be counted in thousands. The Japanese artist is like a good, well-educated, honest and light-hearted child. He has a joyous faculty of loving, observing, and remarking, which ancient and worn-out races lose through the pre-occupation after the work and toil and thought of centuries. The smallest thing amuses him—things which we pass over without noticing. He opens his great intelligent eyes before the splendour of nature. At the age of eighty was not Hokusai as receptive—to employ an ugly modern word—as a young child ? The exuberance of the old man surprises us ; it ought also to touch us. Nothing has tarnished the brightness of his gaiety and his wit. The world is a great garden in which he plays in innocence, making charming posies and watching the flight of the butterflies.

Every one must at any rate gather from the Man-gwathe two following lessons : —

- The union between the greater and the industrial arts should be of the closest, and be in no way humiliating to the painter.

- Love of nature and a continuous study of the humblest objects in the world make art fruitful and render it infinite. A quarter of an hour of real emotion is worth a whole day of over scrupulous study. Flowers are as worthy of study as men.

ARY RENAN.

See Ary Renan’s first article on Hokusai here